Several risk factors contribute to EoE pathogenesis

The incidence of EoE has increased rapidly in recent years. A recent paper pooled the global incidence and prevalence of EoE from 40 studies, which included patients (n=147,668) from 15 countries. Between 2011 and 2013, the prevalence was 32 cases per 100,000 inhabitant-years, which increased to approximately 74 cases per 100,000 inhabitant-years between 2017 and 2022, and was higher in adults than in children.13 However, the prevalence of EoE varies geographically, with higher rates reported in Australia, North America and Western Europe than Japan and China.14 The rising incidence suggests that environmental factors, and their interaction with the oesophageal epithelium, play an important role in disease pathogenesis.4,6,8,14

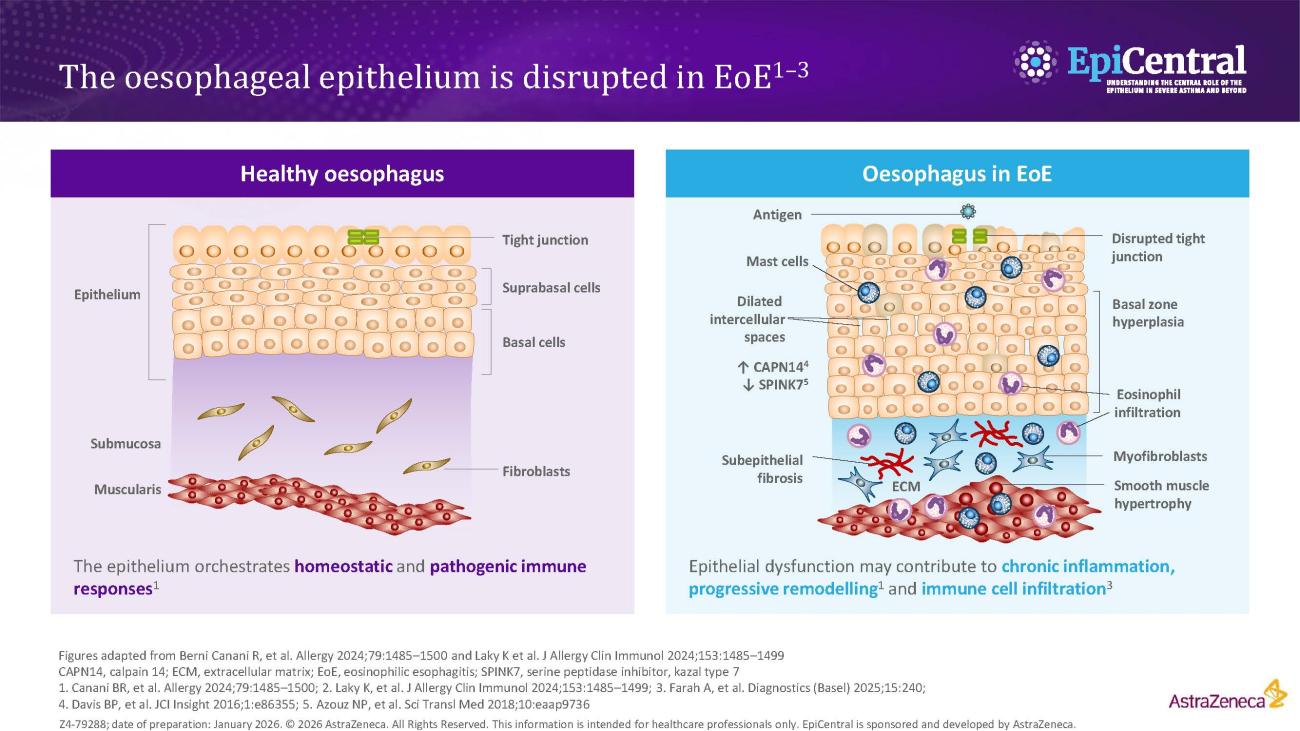

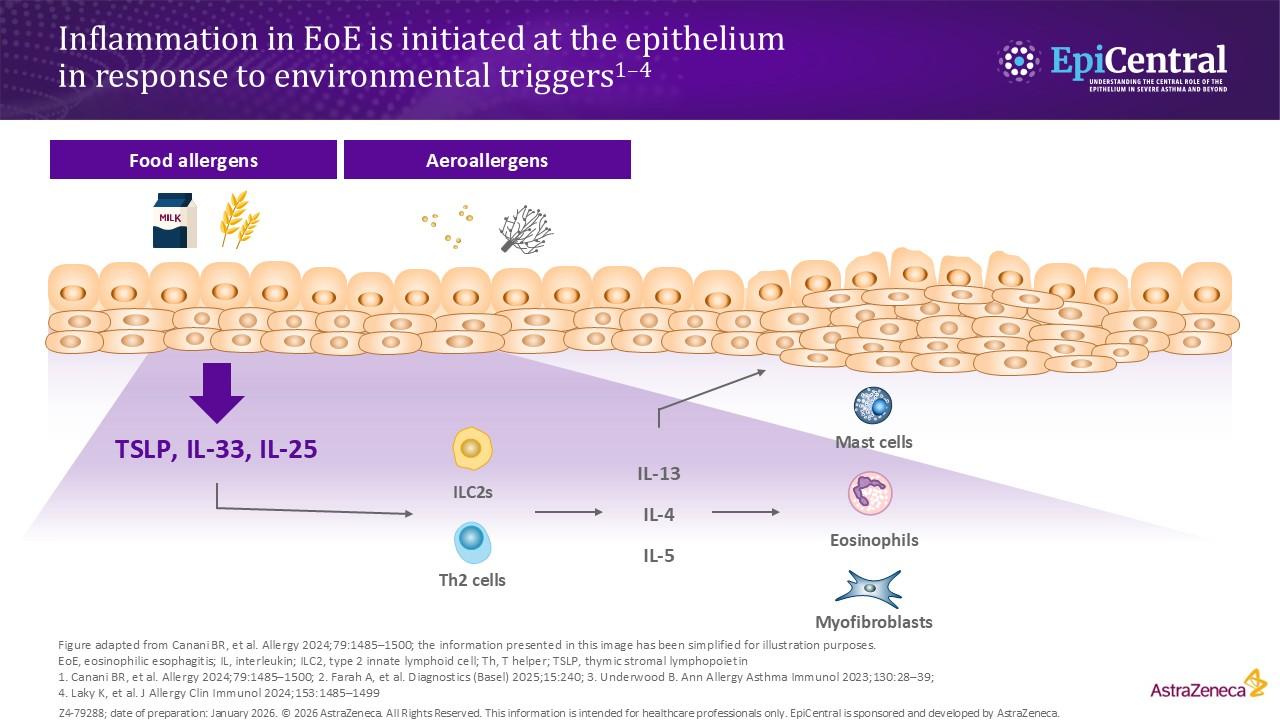

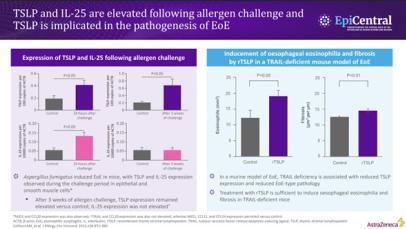

Ingested food allergens, including cow’s milk, wheat, soy and eggs, are known triggers of epithelial dysfunction and T2 inflammation in EoE, and are considered to be risk factors and drivers of the disease.4,8,14 A disrupted epithelial barrier permits allergen penetration and subsequent immune activation.8 Although food allergens are known triggers of EoE, the mechanisms behind allergen-specific immune activation are not fully understood and further research is needed. However, the removal of specific foods, either by dietary elimination or use of hypoallergenic formulas, can lead to disease remission.14

The involvement of aeroallergens, infectious disease and microbiome-altering factors in infancy (including antibiotic use during the first year of life, Caesarean delivery and pre-term birth, use of acid suppressants or a stay in a neonatal intensive care unit) have been also been implicated in several studies.14,15 Although these factors are being investigated for a possible role in EoE, they have not yet been defined as proven risk factors for EoE.15

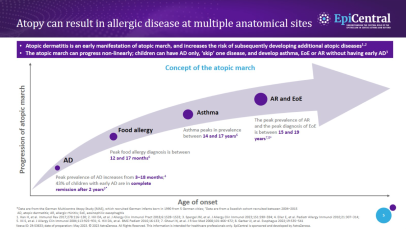

It has been established that EoE is over five-times more likely to occur in people with atopy, and the more atopic comorbidities a patient has, the more likely they are to have EoE.16,17 Much like EoE, atopic diseases, such as asthma, feature a disrupted epithelial barrier, which initiates and drives long-term T2 inflammation and leads to clinical symptoms.4,18 Previous research suggests that between 60% and 80% of patients have concomitant allergic conditions, including IgE-mediated food allergies, asthma, atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis;4 therefore, the more atopic comorbidities a patient has the more likely they are to have EoE.4,17,19,20 This highlights the importance of evaluating patient history when making a diagnosis.

The importance of the epithelium and its interaction with the environment in disease pathogenesis has also been seen in children with EoE. A recent study assessed for concurrent skin and esophageal dysfunction by evaluating ceramide levels in the skin of paediatric patients with EoE. Skin lipid composition of paediatric patients with EoE, but without atopic dermatitis (n=21), were compared with non-atopic dermatitis, non-EoE controls (n=17). It was found that the skin of patients with EoE have significant deficits in ceramide levels, particularly ultralong-chain fatty acid-containing ceramides, compared with the controls.21 This finding supports the suggestion that unified epithelial barrier dysfunction may underlie both skin and oesophageal atopic diseases.21